Feature

Expert, Mubarak decries delayed Harmattan, rising hot whether in Northern Nigeria

….,,Says December is No Longer Cold in Northern Nigeria

By Mubarak Mahmud, PhD

A climate change expert, Mubarak Mahmud, PhD, a Nigerian based in France has decried the rising hot whether in the Northern part of Nigeria, especially in Kano state.

Mubarak, who carried out a project on changes in seasonal cold, emphasized the reasons why December is no longer cold, revealing that Africa is warming faster than the global average.

The expert, Mubarak who cited France National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment

December 2026, said there was a time when December in Northern Nigeria announced itself unmistakably.

And that, Mornings were cold enough to sting the skin. Dust haze blurred the horizon. Nights demanded blankets, not fans. The Harmattan had arrived, right on cue, as it had for generations.

Hazy road in Northern Nigeria (Kano)

What should be the peak of the Harmattan season now arrives without its most familiar signature. The absence of cold dust haze in parts of Northern Nigeria reflects a weakened or delayed Harmattan, leaving December unusually hot rather than cold.

This year, that certainty is gone.

Across the north, December has felt uncomfortably hot. In cities like Kano, the familiar “hazo” that once defined the season is largely absent. Elderly residents who have lived through droughts, floods, and political upheavals say they have never experienced a December like this. Meanwhile, in Lagos, rain has fallen during a period that locals have always known to be dry.

These are not coincidences, and they are not exaggerations. They are signals.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Africa is warming faster than the global average. This is not because the continent emits more greenhouse gases, but because Africa’s geography and climate systems amplify global warming more strongly than most regions on Earth.

Africa is overwhelmingly land, with very little internal water to buffer heat. Land warms faster than oceans and cools less efficiently at night.

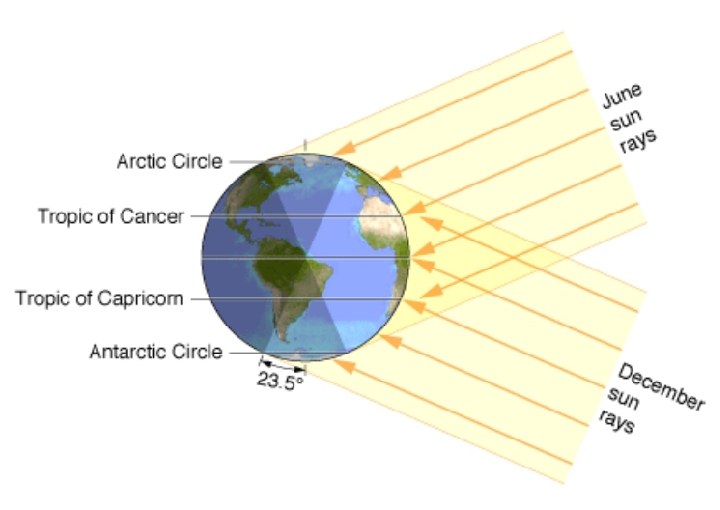

Additionally, much of the continent lies in the tropics, where sunlight strikes the surface more directly and consistently throughout the year.

Large areas experience overhead sun passages that deliver intense solar energy, especially when skies are clear and humidity is low.

In short, Africa absorbs heat efficiently and once that heat is trapped by greenhouse gases, it lingers.

For Northern Nigeria, this warming collides directly with a system that once provided relief: the Harmattan.

Earth–Sun geometry and why the tropics receive stronger sunlight

This diagram shows how Earth’s 23.5° tilt causes the Sun’s rays to strike the tropics more directly than higher latitudes. Between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, sunlight arrives at a steeper angle sometimes directly overhead concentrating more energy at the surface.

This geometry helps explain why tropical regions, including much of Africa, absorb more solar heat and are especially sensitive to global warming.

The Harmattan is a dry, northeasterly wind that blows from the Sahara Desert toward the Gulf of Guinea, traditionally setting in around November. Its power lies not in blocking the sun, but in drying the air.

Dry air allows heat to escape rapidly at night producing the cold mornings many Nigerians remember. The dust it carries reflects a portion of incoming sunlight and signals the strength of the circulation.

Satellite view of Saharan dust plume over the Atlantic

Satellite imagery shows Saharan dust being lifted and transported westward over the Atlantic, evidence that dust generation still occurs, even as weakened Harmattan winds increasingly fail to carry it deep into West Africa.

But the Harmattan depends on a precise balance. The Sahara must cool sufficiently after summer to build strong high pressure. Also, the West African monsoon must retreat southward. The pressure contrast between north and south must be sharp enough to drive sustained winds.

Climate change is weakening all of these conditions at once.

The Sahara now cools later in the year, delaying the formation of the high-pressure system that drives Harmattan winds.

Moreover, the monsoon lingers longer, keeping moisture in the atmosphere and resisting dry air intrusion.

The Atlantic waters off the coast remain warmer, sustaining humidity and low pressure. By the time the Harmattan establishes itself, it often does so weakly and briefly.

That is why Kano can have dry air but no dust haze, warmth without relief, and December nights that no longer cool. No strong Harmattan wind means no hazo and no seasonal reset.

In Lagos, the story is different but connected. The Harmattan has never dominated the coast the way it does inland.

Therefore, when monsoon moisture lingers and ocean temperatures rise, convection can still occur, producing rainfall during months that older climate patterns labeled “dry.” The result is rain at the “wrong” time not because the seasons are random, but because their boundaries are blurring.

Flooded street in Lagos

Warmer ocean waters and lingering monsoon influence are blurring seasonal boundaries along Nigeria’s coast.

It is important to say clearly what this does not mean. This does not mean the Harmattan will now extend into April. Spring solar heating is too strong, and the atmospheric system inevitably shifts toward the hot pre-monsoon season.

Climate change is not stretching the Harmattan; it is compressing it, making it shorter, weaker, and less reliable.

What Nigerians are experiencing is therefore not confusion, but transition.

Local climate knowledge, passed down over decades, was built on a stable system. That system is changing faster than memory can keep up. When elders say, “This never used to happen,” science increasingly agrees with them.

Nigeria must begin to treat these signals seriously not as passing anomalies, but as evidence of a climate reality that will shape health, energy use, agriculture, and urban planning in the years ahead. Hotter Decembers, missing dust haze, surprise rains, and warmer nights are not just discomforts. They are warnings.

The Harmattan has not vanished. But it no longer arrives as it once did, and the climate that sustained its reliability is slipping away.

Ignoring that truth will not bring the cold back. Understanding it is the first step toward preparing for what comes next.